Books mentioned in this post: Fred Moten, Black and Blur (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017), Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory; trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997).

Why no posts lately? I was way too taken up by the political season from the summer through November, but do I really have that as an excuse? No, I’d say it was more a silence from a buildup of too many things to say and not enough confidence to say them. I want to see me be brave! OK, Bareilles self-help dose applied; let’s get into it.

I have been listening to plenty of new music, from new pop picks by my students, to an ever-expanding range of Mahler, to Bruckner and Czech composers inspired by my 1,100-mile contact high from the residency of the national orchestra, to, like everyone else in jazz-world, the newly released Joe Henderson live recording, to solo records from Fred Hersch and Craig Taborn, to Fred Hersch playing live with Joe Henderson in the 80s (thanks, YouTube), to Patricia Brennan and Adam O’Farrill, and Kris Davis, and closer to EC home, the Nunnery, Dosh, Humbird, and an expanding group of friends. I’m within spitting distance of finally having a new “symphonia” (3-part invention) fully under my fingers. I have started in on my first Ligeti etude (never too old to start one). Getting Mozart’s most ostentatiously brilliant and gorgeous violin sonata happening, on violin, and looking forward to adding electrification to the range of possible things I can do with my fiddle.

Lots of musical collaborations planned, and a new version of my “burning down the house” class planned for the spring. Looking to get that a bit better grounded in intellectual history, just because—well, it’s the second time I’m teaching it so, time to get a little more serious. My record coming out in April and a bunch of shows planned around that, along with an effort at a publicity campaign (don’t worry, not planning to have that much in the stack—I know how annoying this gets!) Planning to begin doing a bit of jazz teaching, and thus am expanding my net for jazz learning, pedagogical approaches, trying to absorb more, expand my base of operations, be up on the major theories and start thinking about what I think about these things myself. And then begin the project of expressing those views in ways that other folks might find of use.

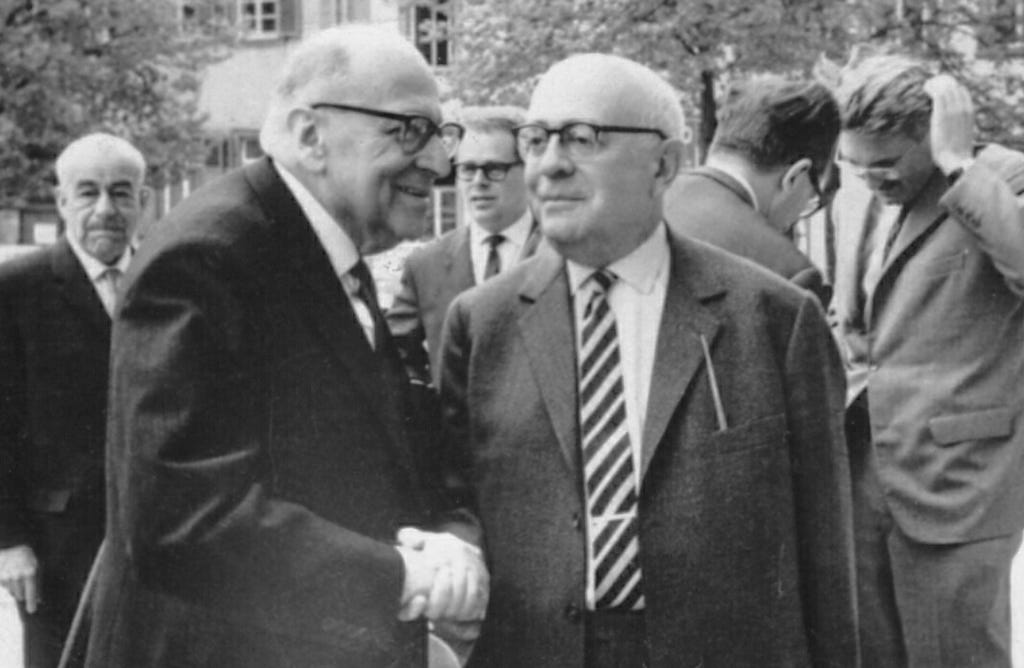

And: I’ve found my way to an interesting thread in jazz-music-theory world, where someone is thinking about jazz and improvisation with Theodor Adorno. The someone is Fred Moten, NYU professor and the first person my literature-professor friends recommended to me when I said “jazz theory.” It’s tricky doing jazz Adorno, as Adorno famously dissed jazz.1 It’s also tricky doing anything Adorno, as Adorno famously wrote like one not wanting quite to be understood. But, I’ve got a history here, and I have found grappling with him to be consistently generative. It’s in my Rosalind book in a significant way: I took what he had to say about some nineteenth-century German poetry and music to help me get to to the way I wanted to think about late sixteenth-century English poetry. So I’m ready to forgive Adorno’s difficulty, and his perverse opinions, because I’ve found he generally provokes better thought in me.

Which gets us to Moten, writing in a collection of his essays published in 2017 by Duke University Press under the title Black and Blur. There are 25 chapters of variable length in the book’s almost 350 pages, and also 50 numbered sections that overlap with the chapters. It’s a book that speaks high theory, so I’m using of a variety of techniques to access the headspace, like picking up mid-chapter, rather than trying to proceed from beginning to end. Thus I dropped into a chapter called “Taste Dissonance Flavor Escape (Preface to a Solo by Miles Davis),” where I encountered Moten addressing an Adorno essay that I did not know, namely “On Some Relationships between Music and Painting.”2

What rapidly develops is a set of terms where painting and music speak to each other, we consider dimensions of space and time, into which theories of improvisation and composition are also interpolated. So, for example, this:

I want to consider improvisation as precisely that material graphesis which is, for Adorno, essential to the syntax, the articulation of individual detail, that makes the organized whole a possibility. Composition is imagining improvisation—quasi una fantasia. Improvisation is the animative, electric, hieroglyphic-seismographic tension that cuts the pose while also being the condition of possibility of the whole in its unavoidably narrative, unavoidably fantastic theatricality. (82)

It’s terrible of me to have taken this out of context, but—the point is to find a way in, so context can wait. What I like about this is that Moten seems to be using Adorno to theorize improvisation in areas that interest me—i.e., “modern jazz music”—even as the passage that he quotes from Adorno just before this seems to say that musical progress has gone in just one direction, from the “laxness” of non-written, improvised music, to the “articulation” of “highly-organized” music, which is to say the kind he likes (Adorno, “Relationships,” 70). That is, Moten seems to be using Adorno to theorize positively music that Adorno famously despised.

Almost the first full page of Moten’s bibliography is devoted to citations of Adorno, meaning that this book seems significantly engaged with this writer, meaning, I’m very interested in moving out from this almost random stopping point and following Moten, and Moten’s Adorno, a lot farther.

Another thing that is exciting about that Adorno essay is that it mixes painting and music, which I am about to do again with a group of intrepid students in my spring class on artistic revolutions. How happy I was to find that Adorno also seems to have had a good deal to say about Mahler, and that the very first reference I found in Adorno’s forbidding, fascinating book, Aesthetic Theory, is this:

But works can be actualized through historical development, through correspondence with later developments: Names such as Gesualdo de Venosa, El Greco, Turner, Büchner are all famous examples, not accidentally rediscovered after the break with continuous tradition. Even works that did not reach the technical standard of their periods, such as Mahler’s early symphonies, communicate with later developments and indeed precisely by means of what separated them from their own time. Mahler’s music is progressive just by its clumsy and at the same time objective refusal of the neo-romantic intoxication with sound, but this refusal was in its own time scandalous, modern perhaps in the same way as were the simplifications of van Gogh and the fauves vis-à-vis impressionism. (41)

What I think this might be saying is that Mahler’s apparent musical “simplifications” in his early symphonies, scandalous (like punk?!) in its time, look later to be ahead of their time via the “communication” with “later developments.” And he clarifies the move through analogy with—painting! OK, super-exciting.

So anyway—in 2025 I’m definitely planning to continue writing about new music, but also to try to get farther in connecting my work to ongoing conversations in various places. In “the jazz press”? Of course (for example, Ethan Iverson weighing in recently on Daniil Trifonov’s versions of Bill Evans and Art Tatum), but also in more academic conversations, especially ones that might connect productively with my academic past. Engaging more with Moten-Adorno looks like it should help with that.

Adorno’s essay, “On Jazz,” is easiest to access for English-language readers in the collection, Essays on Music, edited by Richard Leppert (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002). I’m working here with the same translation, by Jamie Owen Daniel, published first in the 1989-90 issue of the journal Discourse. Adorno’s German original was published under the pseudonym Hektor Rottweiler in the journal Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, in 1936 (note that the journal, an organ of the Institute for Social Research, was published in France, the Institute having moved out of Germany following Hitler’s rise to power in 1933), and then republished in a collection of his essays called Moments Musicaux, in 1964. Whew.

A slightly easier time here: my translation, which is also Moten’s, is by Susan Gillespie, published in The Musical Quarterly 79, no. 1 (1995): 66–79. The original essay appeared in a festschrift for Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler in 1965, and then again in volume 16 of Adorno’s German collected works, in 1978.